As a Buddhist who practices hatha yoga, I often wonder what the differences are between the yogic scriptures and Buddhist teachings.

Buddha lived in India 2,600 years ago so it may be no surprise that his teachings bear some similarities to the Hindu tradition in which he lived. In a similar way that Jesus’s teachings build on but differ from the Judaism into which he was born, so Buddha found a new way that didn’t entirely deviate from the tradition which went before him but was different enough that it couldn’t simply be said to sit within that same tradition.

So, what are those similarities and differences and what do they mean for practitioners?

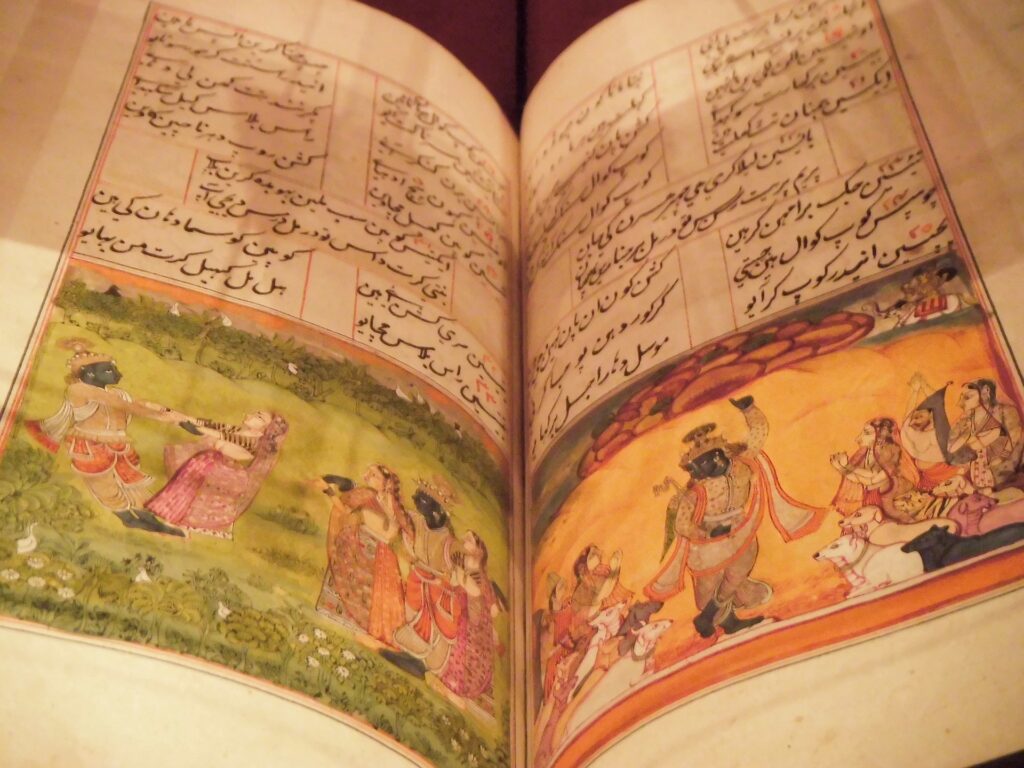

Yogic and Buddhist texts

The Bhagavad Gita is seen as the central text of yoga which tells the practitioner how to live. Buddhism has no such central text. My understanding of it is shaped very much by Tibetan Mahayana teachings so that is the “Buddhism” I will compare it to.

Similarities

Both share a basic grounding in non-duality as the way to ultimately understand reality. To recognise, as the Gita says,

“You were never born; you will never die” (chapter 2, verse 20)

and that

“I am not the doer” (chapter 5, verse 8)

Buddha would no doubt agree with these statements. This understanding of non-duality leads to many similar suggestions on how to live and how to practice, with both recognising non-attachment and equanimity as being the way to live and the attitude to take towards everything in life. Selfless actions bring good karma, and selfish acts bring negative karma they both agree.

Differences

But exactly what is unborn and cannot die differs. For the yogi, the self is never born and cannot die, and is immortal. For the Buddhist, it is the mind or consciousness that goes from life to life because for the Buddhist there is no self. This is the major difference between the Buddha’s teachings and those he came from. He recognised that non-duality means that there is no “it”-ness, no “thing” at the centre of any phenomena, including this body and mind. There is no self, he declared in his second teaching after becoming enlightened. Upon hearing this, it is said that some of the disciples listening to him became instantly enlightened.

This distinction then creates differences in the way that Krishna and Buddha tell their followers to practice. For the Buddhist who recognises there is no self, huge compassion arises for sentient beings because we see the way in which this belief in a self causes the very suffering we are all constantly trying to avoid. The Buddhist renounces the world in order to develop wisdom and compassion so that they might benefit all these suffering sentient beings. But for the yogi, the path is to connect to the self (atman) and in connecting to the self they connect to God (brahman). The path is not renunciation but selfless action to benefit the world.

Practice

The attempt to recognise that there is no self (the Buddhist) or to connect to the self (the yogi) are then attained through subtly different styles of meditation. Whilst the Buddhist renounces the material world and the yogi embraces it, the meditation practices do the opposite as far as I can tell. Krishna advises that

“the wise can draw in their senses at will” (ch2, verse 58).

“Strive to still your thoughts” (chapter 6, verse 12)

he advises and concentrate single-pointedly so that

“the mind will become stilled in the self” (chapter 6, verse 25).

In this way, the one who is engaged in the world distances him/her self from the senses and connects to the self within (atman) as a way to connect to God (Brahmin). This union, the aim of yoga, leads to freedom and immortality.

For the Buddhist, one does not want to disconnect from the world. If there is non-duality then samsara is nirvana and nirvana is samsara and one cannot be liberated from samsara by withdrawing from it. To withdraw would be to continue to act in the same way we always have that keeps us trapped in samsara, resisting pain and moving toward pleasure. One must live in samsara and stop believing and buying into the duality. The meditation practice therefore is to keep the senses open and settle the mind. The meditator is alive to all the sense but doesn’t get caught up in them. In this way, the Buddhist abides in equanimity, cutting through duality and seeing through the self and the empty nature of all phenomena by resting in the open awareness that is consciousness itself (one’s own Buddha nature) thus freeing oneself from the ignorance that keeps one bound in samsara.

Are they really different?

The differences outlined above are in the way things are conceptualised, theorised and practiced. Whether this ultimately leads to different states of mind and whether the experience of Brahmin and enlightenment are the same or different is for far more realised beings than myself to discuss, for they have tasted nirvana and/or Brahmin for themselves.

I don’t believe the much-repeated truism that all religious teachings point to and lead to the same place, for the absolute may well be beyond concepts but are all absolutes the same experientially? The concepts we use to point to the absolute matter. If they didn’t, why did Jesus and Buddha feel the need to lay out their teachings using different concepts to those in their established tradition to point at the absolute in a different way? Is the experience of zero, the same as the experience of Brahmin, the same as the experience of the Christian God, the same as enlightenment? I’m willing to be convinced, but only by those who are speaking from far more than a theoretical position.